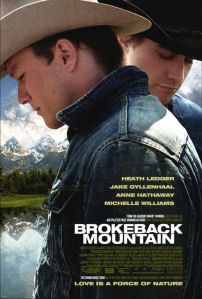

In honor of Gay Pride weekend here in NYC, it’s time to revisit the groundbreaking Brokeback Mountain.

In honor of Gay Pride weekend here in NYC, it’s time to revisit the groundbreaking Brokeback Mountain.

Annie Proulx’s short story, Brokeback Mountain, first appeared in The New Yorker in 1997. The tentative love story of two cowboys (Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal) in the 1960s played against stereotypes and caused a sensation. (The story later capped Proulx’s 1999 collection, Close Range: Wyoming Stories, which was shortlisted for the Pulitzer Prize.)

Producer and co-writer Diana Ossana and Pulitzer Prize-winner Larry McMurtry (Lonesome Dove) fleshed out the spare story, adding the wives (Michelle Williams and Ann Hathaway). Director Ang Lee (Sense and Sensibility, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) proved to be a masterful stroke.

Lee brings subtlety and sophistication to the story, eliciting top-notch performances all around. Rodrigo Pietro’s stunning cinematography (with Canada substituting for Montana) and Gustavo Santaolalla’s guitar-driven, Oscar-winning score add to the poignancy of the love story.

Santaolalla’s music makes a distinct impression, due to his duties as music producer, writer and instrumentalist. In addition to composing the score, he co-wrote songs performed by Mary McBride, Jackie Green, Teddy Thompson, and Emmylou Harris. The latter’s song, “A Love That Will Never Grow Old” (lyrics by Bernie Taupin), won a Golden Globe as Best Song but was ineligible for Ocar consideration because of its short screen time.

Santaolalla began working on the score after reading the script and the short story. “Ninety-nine percent of the music…I wrote before the movie was shot.” He sent Lee some of his ideas after their original conversation. “He thought I was sending him stuff I had previously composed, and so he told [Brokeback producer] James Schamus, ‘What a pity we can’t use this, it would be perfect for our movie.’ And then James said, ‘But Gustavo did write this for us.'”

“(Lee and I) both had the idea for acoustic guitar and strings,” Santaolalla said. “I thought it would be great to have one more element.” That element was the pedal steel guitar. On the soundtrack, the instrument is played by Bob Bernstein, former Senior Vice President of Corporate Communications at Universal Music Group, whose earlier gig as an in-demand country music sideman served him well on the score.

The Hollywood Reporter said “the film benefits enormously from [the] melodic and plangent score.” Variety gave the score faint praise, calling it “conventionally supportive…nicely abetted by a host of period and setting-appropriate tunes.” Michael Phillips from the Chicago Tribune, however, wished Santaolalla had restrained himself: “Once Ennis and Jack get off on their own the movie nearly drowns in orchestral strings.”

From its initial successes at the Venice, Telluride, and Toronto film festivals, Brokeback Mountain rode a wave of critical and surprising audience attention. The fact that it won more critic awards for Best Picture than any other film of 2005 makes its Oscar loss to Crash that much more perplexing and frustrating.

There’s no doubt that Santaolalla’s brief score rode in on the Brokeback stampede. His win has caused much karping on film score message boards, second only to his win the following year for Babel. Whether or not Santaolalla deserved his Oscar is up for debate. Whether or not the music poignantly captured the characters’ loneliness, wide open spaces, and “a love that will never grow old” is not.

Posted by Jim Lochner

Posted by Jim Lochner